Lula Government Delays Tobacco Growing Phase-Out Program

The initiative has been sitting in the minister of Agrarian Development’s office since December 2024. Without support from public policies, farmers in tobacco-growing regions face losses when trying to invest in other crops.

Farmer Paulo Sérgio Padilha, 53, has been growing tobacco since he was seven years old. But after this harvest, he plans to sell the 33 hectares of land where he lives with his wife and walk away from the crop for good. He will leave behind citrus orchards, corn, beans and potatoes, cattle, and a small preserved-foods agribusiness—alternatives to tobacco that he unsuccessfully tried to make viable. In the mountain area of Sinimbu – a municipality of 10,000 inhabitants in central Rio Grande do Sul – if the plan is to give up tobacco cultivation, the simplest answer is often pack up and move out.

Years ago, the farmer even held organic certification and sold grains and vegetables for school lunches. Starting in 2016, when public funding for federal programs such as the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) and the National School Feeding Program (Pnae) dwindled, the only customers left were the tobacco companies. “There was a time when we delivered 500 kilos of sweet potatoes every week to the cooperative and sold them for US$ 0,36 a kilo, so it was worth it. But then they started asking for only 18 or 20 kilos, ” Padilha recalls. “That’s why we had to go back to tobacco. ”

In the region where he lives, the land and roads are uneven and rugged, surrounded by slopes and cliffs, which makes it difficult to transport any production that does not already have an established logistics chain, like tobacco.

“What sustains this crop and guarantees tobacco on the property is the market: you’re certain they will buy it, even if you don’t know for how much you’ll sell, ” explains Padilha, who this season intends to grow his last 50,000 tobacco plants for Alliance One, a multinational that supplies tobacco leaf for Chinese cigarettes and other major companies, such as Japan Tobacco International (JTI, maker of Camel) and Philip Morris International (Marlboro).

At the end of June, farmer Paulo Sérgio Padilha’s tobacco seedlings are being prepared for planting on his property in the hills of Sinimbu, countryside of Rio Grande do Sul (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

The Brazilian Tobacco Growers Association (Afubra) estimates there were over 138,000 tobacco producers in the 2024/25 harvest, most of them family farmers from the South, like Padilha. Two decades earlier, in 2004/05, that number was about 236,000.

The same trend is seen in foreign trade. Brazil, the world’s largest exporter of tobacco leaf, shipped 446,000 tons abroad in 2024 — down 28% from 2005, according to the Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade, and Services (MDIC). The decline reflects a global drop in cigarette consumption, driven by public health measures.

Negotiated in the early 2000s, the global Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) — coordinated by the World Health Organization (WHO) and ratified by 192 countries — is partly behind the drop in demand. Brazil joined the treaty in 2006, but only after facing fierce resistance from the tobacco industry and farmers. As a result, when signing it, the Brazilian government promised to create policies to support farmers in diversifying their crops into alternatives to tobacco, given that efforts to curb cigarette use would lead to a reduction in demand for the leaf.

Nearly two decades later, those alternatives remain elusive. Aging farmers, no longer able to handle the grueling labor tobacco demands, often lease or sell their land. Their children have little interest in rural life, let alone tobacco farming. Larger producers snap up smallholdings, shifting the profile of family farming — once based on tobacco, poultry, and subsistence crops — toward large-scale commodities like soybeans.

According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 41% of the planted area in Sinimbu in 2003 was devoted to tobacco, with not a single square meter planted with soy. Twenty years later, in 2023, tobacco still covered 35% of the municipality’s farmland, while soy had expanded to nearly 19% of the total. In the same period, the area planted with beans, for instance, shrank from 7% to just 2%.

Farmer Paulo Sérgio Padilha invested about R$100,000 in a preserves and pickling business, but the equipment and products now sit abandoned (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

The industry itself offers little help. Tobacco companies and rural associations tend to view diversification programs as “attacks” aimed at “eliminating” tobacco farming — the primary source of income for family farmers in several southern regions of Brazil. At the same time, the sector insists that small producers are not dependent on the crop. The strategy is to portray any public policy linked to tobacco control as a direct blow to tobacco growers — and, by extension, to family farming.

“It becomes ingrained in farmers’ minds that tobacco is the only crop capable of generating income and profit on a small property, ” says geographer Virgínia Etges, a professor at the University of Santa Cruz do Sul (Unisc) — a city that hosts the headquarters of the industry’s main companies. “And they shut themselves off to anything else. ”

According to Afubra, tobacco accounts for an average of 56% of growers’ gross income, with food crops and livestock making up the remainder. In practice, though, much of this so-called “alternative” production is destined for the farmers’ own tables.

In 2005, the federal government launched the National Program for the Diversification of Tobacco-Growing Areas (PNDACT), aimed at helping farmers transition from tobacco to other sources of income as part of negotiations under the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). The initiative sought to cushion the impact of declining cigarette demand on Brazil’s tobacco sector. Implemented in a few editions, it relied on contracted organizations to provide technical assistance to families in search of alternatives. But the program never took off.

“We have producers who had completely stopped growing tobacco but returned after some time out of necessity, ” says Vilmar Sergiki, president of Ceasol, an organization that implemented the PNDACT in the São João do Triunfo region of south-central Paraná. In his view, the absence of a guaranteed-purchase market for other crops remains a major obstacle to this transition — underscoring the need for broader policies.

In Brazil, tobacco companies operate under an integrated system in which they “contract” rural producers to supply them with the leaf. Under this arrangement, the company orders a specific number of tobacco plants from the farmer, provides inputs — such as seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers — offers technical guidance, and guarantees the purchase of the ordered volume at the end of the harvest. The catch: the final price is reduced by the cost of those inputs, which are not given for free. If the farmer fails to deliver the agreed quantity, they end up in debt.

Advance sales offer farmers a sense of security, drawing many back to tobacco cultivation at the first hint of instability in other markets, such as grains, vegetables, or dairy. “Tobacco also has its price fluctuations, but at least it guarantees the sale — even if poorly, ” says Sergiki.

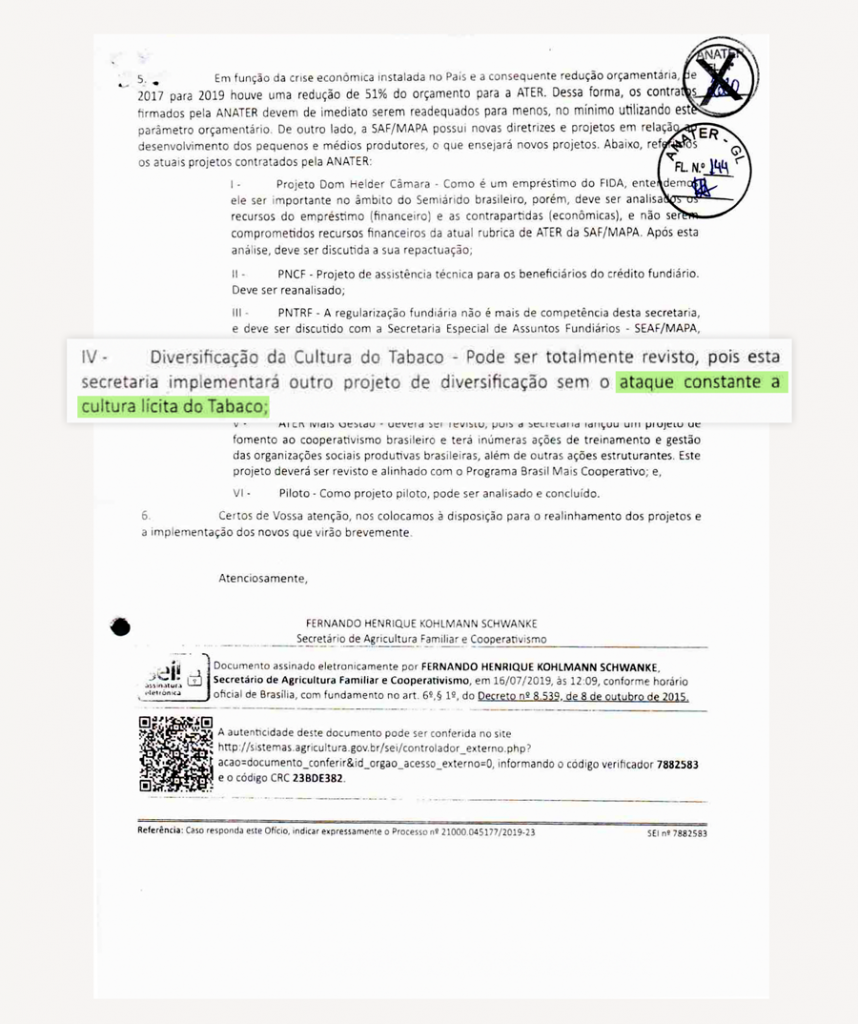

In 2019, the Jair Bolsonaro administration suspended the diversification program, calling it “a constant attack on the lawful culture of tobacco, ” according to a letter from the Ministry of Agriculture at the time, reviewed by Joio. The initiative has been frozen ever since.

In early 2024, during the latest Conference of the Framework Convention, the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA) even announced the resumption of the PNDACT. But the measure has been stalled in Minister Paulo Teixeira’s office since December of that year. When questioned, the ministry dodged explaining the reason for the delay. Speaking to Joio, the ministry promised to relaunch the program by March 2026.

In April this year, the Federal Audit Court (TCU) released an audit that flagged several problems in MDA initiatives, including the absence of clear project guidelines, contracts and partnerships with incorrect timelines, and failures in monitoring outcomes. Unsurprisingly, little data exist on the most recent editions of the PNDACT—such as whether producers returned to tobacco once the projects ended, or whether alternative crops proved successful.

Padilha tried selling vegetables and potatoes, and invested in a small preserved-foods agribusiness, but eventually had to return to cultivating tobacco. In order to leave the tobacco bussiness, he decided to sell his rural property (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

According to Freedom of Information Act (LAI) requests made by reporters, the only evaluation document available at the ministry is a nine-page report covering calls for proposals implemented between 2018 and 2023. Without offering details, the report claims that nearly half of the 1,200 tobacco farmers who benefited had replaced tobacco with corn as their “main activity,” supposedly proving the program’s success. Dairy farming, horticulture, and bean production also appeared as alternatives in other cases. The report does not specify, however, in which regions these crops took hold, how much income they generated, or whether tobacco was in fact abandoned on those properties.

Speaking to Joio, the National Agency for Technical Assistance and Rural Extension (Anater), which was responsible for implementing the latest editions of the diversification program, said that “through its Technical Directorate, it has not received any guidelines or official communication regarding a new tobacco diversification program” to date. The agency also stated that it carries out its programs and actions based on the objectives, target audiences, territories, and resources defined by the MDA.

The ministry has drawn up a work plan to address the problems identified by the TCU audit, which includes negotiating a new “management contract” between the MDA and Anater by December this year. The relaunch of the PNDACT is expected to take place only after this document is signed, since the agency will be responsible for implementing it. According to the ministry, the program guidelines are in their final drafting stage.

We in civil society have long called for this program to be resumed because, although it gained international recognition for a time, it was greatly weakened,” says Mônica Andreis, director of the NGO ACT, which advocates tobacco control measures. “We welcomed the announcement of its resumption, but we have yet to see it materialize.”

Even so, the plan under discussion remains modest. The pilot project is expected to serve 300 family-farming households in the South through calls for proposals and public tenders for technical assistance, in a format similar to previous editions. Funding has been earmarked—around R$3 million, according to ministry officials who spoke to Joio in April. That is far below previous levels, when PNDACT calls reached R$26 million and supported up to 7,000 farmers, as in 2018.

When asked, the MDA did not explain why the diversification program has yet to be relaunched. In a note, the ministry said only that “the matter is being handled with the seriousness and responsibility required, considering the challenges and necessary coordination.” The ministry also declined to address the TCU audit findings, saying merely that it was unaware of any audits “specifically” or “directly related” to the PNDACT

Even so, the plan now under discussion is modest. The pilot version would serve just 300 family-farming households in the southern region through public calls for technical assistance, following a format similar to previous editions. Funding has even been earmarked—around R$3 million, ministry officials told Joio in April. That is a small amount compared to previous years, when PNDACT calls for proposals reached R$26 million and supported up to 7,000 farmers, as in 2018.

When questioned by reporters, the MDA did not explain why the diversification program had yet to be launched. In a statement, the ministry said the issue “is being addressed with the seriousness and responsibility required, considering the challenges and necessary coordination.” The ministry did not address questions about the TCU audit, which highlighted long-standing management failures, saying only that it was unaware of any audits “specifically” or “directly related” to the PNDACT.

The cattle graze around Padilha’s house, on the property that the farmer maintains with his wife in the interior of Sinimbu (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

While the government’s program to support tobacco growers remains on hold — awaiting approval from a sector unlikely to grant it anytime soon — the cigarette industry has pressed ahead with its own initiatives. In late March, the Interstate Union of Tobacco Industries (SindiTabaco), which represents tobacco companies in southern Brazil, unveiled an updated version of a project first launched in the 1980s by the now-defunct Souza Cruz, today British American Tobacco (BAT). Back then, the goal was to encourage farmers to plant corn or beans in the off-season. The rebranded initiative now goes by the name “Tobacco is Agribusiness: Diversification of Farms”.

At the launch event — held in a small, 30-seat auditorium during Expoagro Afubra, one of Rio Grande do Sul’s main agricultural fairs — union president Valmor Thesing framed the new program as part of the sector’s mobilization ahead of this year’s FCTC meetings, where member countries periodically debate anti-tobacco measures. “We are in a COP [Conference of the Parties, under the FCTC] year, and they are already announcing that they will attack the entire production chain again, ” Thesing said. “First, they claim tobacco production must be eliminated because producers are not diversified — that’s a lie! ”

In June, Joio asked the union to put reporters in touch with farmers who had already taken part in the new program so they could explain how it had helped them plant other crops. SindiTabaco, however, declined to refer anyone or provide further details on how the project works.

According to Sergio Padilha, this type of “incentive” for diversification usually amounts to offering grain seeds when ordering inputs at the start of each harvest. As with other agrochemicals supplied for tobacco cultivation, the costs of “diversification” are deducted from the farmer’s payment when the tobacco is sold. “If I’m going to buy transgenic corn, I’ll go to any farm supply store and get it for US$ 109 — the same product the company sells you for US$ 200, ” he says.

Philip Morris operates a cigarette factory in Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil, even as it claims to be committed to a “smoke-free future.” (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

At the same event, SindiTabaco also announced a partnership with the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), a federal government agency. The program, called Protected Soil, will select 33 farms in southern Brazil to test best management practices in tobacco production through 2029. The initiative is adapted from the Auêra Project, a partnership Embrapa has maintained with cigarette maker Philip Morris International since 2019, created to “promote sustainable tobacco production. ”

“This is the logic: strengthen and improve the soil so that we have tobacco with higher productivity and better quality, but also so that we work on crop diversification, ” researcher Waldyr Stumpf told Joio. At the time, Stumpf was head of Embrapa Clima Temperado and signed the cooperation agreement with the union. “We’re not focusing on replacing [tobacco], but rather on having the producer also grow other crops alongside the leaf, because he already has an established market — but we’d also like him to work with beans, corn, vegetables, peaches, strawberries, ” he said.

The initiatives, however, offered no indication of support for marketing these alternative crops — the main obstacle to diversification. “Today, we already have other crops that bring in more money than tobacco, but marketing is the big bottleneck, ” says Sergiki, of Ceasol, who has worked with vegetable and fruit growers — such as lettuce and strawberries — who quit tobacco and never went back. “The farmer knows how to produce, but doesn’t know how to sell. ”

Mayor of Vera Cruz, Gilson Becker has been president of Amprotabaco since March of this year (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

Finding buyers, however, should not be the problem. In the Vale do Rio Pardo — one of Rio Grande do Sul’s main tobacco-growing regions, which includes municipalities such as Santa Cruz do Sul, Sinimbu, and Venâncio Aires — there is actually a shortage of locally produced food to meet demand. By contrast, the tobacco industry’s presence is anything but scarce, with facilities ranging from cigarette factories like Philip Morris and JTI to tobacco processing plants and multinational leaf exporters.

“A large volume [of food] is brought in, for example, from Ceasa in Porto Alegre [a central distribution hub 166 km away] to supply supermarkets here, ” Vera Cruz mayor Gilson Becker told Joio. Vera Cruz, a neighboring municipality of Santa Cruz do Sul, is also home to Becker’s role as president of the Association of Tobacco-Producing Municipalities (Amprotabaco), one of the organizations advocating for the sector’s interests. “So there is a significant market niche that could be expanded, which today still doesn’t have the production volume to meet local demand. ”

According to Becker, Amprotabaco supports diversification but has no coordinated plan to advance such a policy, leaving it to each municipality to decide. In practice, this means that efforts to promote alternatives to tobacco are scattered within the general work municipal agriculture departments and rural technical assistance teams already provide to small farmers — whether they grow tobacco or not.

A greengrocer in Vera Cruz buys fruits and vegetables from a supply center in Porto Alegre—more than 165 km away—instead of sourcing from local producers (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

Until 2019, farmer Valderi de Moura, 59, cultivated about 2.5 hectares of tobacco — roughly 40,000 plants — on his rural property in Sinimbu. Since then, he has leased part of his 23 hectares to neighbors and begun testing citrus production in search of a viable alternative to the leaf. “The idea is to invest in something that has a reasonable return with less labor demand, ” he says. His initial trial will cover about half a hectare.

The initiative is part of a Sinimbu municipal government project involving Moura and eight other rural producers. Each participant received a small municipal grant to invest in fruit crops. “Up to US$ 727, they reimburse half the value [US$ 363],” Moura explains. One of eleven siblings born to illiterate parents, he learned to grow tobacco at a young age. Today, his daughter — who is earning a degree in Agroecology and works at a cooperative and helps tend the orchards, which could also secure a marketing channel for their produce.

For now, Moura’s main source of income is leasing part of his land. But the advance of soybean fields around his property worries him. Some neighbors use drones to spray pesticides, and the former tobacco farmer fears the chemicals could drift into his organically cultivated orchards.

Until he retired from tobacco, Moura was an integrated producer for Continental Tabacos (CTA), a Brazilian tobacco company and subsidiary of U.S.-based Hail & Cotton, which supplies leaf to the global market — just like Padilha’s buyer, Alliance One. Both are among several exporters that keep Brazil at the forefront of global trade in the sector — and both could face challenges as demand for tobacco continues its long-term decline, even as smoking remains strong in populous Asian countries such as China and Indonesia.

A rural producer from the interior of Sinimbu, Valderi de Moura retired from tobacco and is now investing in citrus fruits, such as oranges and bergamots, to try to make his property profitable (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

The rise of electronic cigarettes could hasten that decline, since nicotine from tobacco grown by just a few hundred farmers can supply thousands of vapes. It is no coincidence that leaf suppliers — Alliance One among them — view these new products as a business risk.

“Some of our most significant customers, including Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco [maker of the Kent and Lucky Strike brands], have publicly announced intentions to move toward smoke-free products [vapes, heated tobacco, and pouches] that would replace traditional cigarettes,” states the 2024 investor report of Pyxus, the holding company that owns Alliance One.

“Generally, smoke-free products require less tobacco in their production than traditional cigarettes. The increasing trend of replacing traditional cigarettes with smoke-free products, driven by our customers or consumers, could materially and adversely affect the results of our operations, ” reads an excerpt from the business risk section of the report.

Another major tobacco supplier, U.S.-based Universal Leaf, also addresses the issue with caution. In a 2024 shareholder presentation on the company’s activities, it noted that the “effects on leaf tobacco demand” from new nicotine products are “still uncertain or developing. ” Even so, the company acknowledged that “all major tobacco manufacturers are creating next-generation products” and that these “use fewer tobacco leaves in a strict one-to-one comparison with a combustible cigarette. ” To avoid losing ground in the vape supply chain, the multinational is already investing in liquid nicotine production.

Even so, entities that in theory should defend the public interest such as Amprotabaco — the network of mayors from tobacco-producing municipalities — support the legalization of electronic devices without addressing how this growth could affect tobacco farmers in their regions. Since Brazil exports about 90% of the tobacco it produces, the risk exists regardless of whether the domestic market is legalized. Today, companies like BAT and Philip Morris already earn between 17% and 40% of their profits from “smoke-free products” — and both state in their annual shareholder reports that, by 2035, this new portfolio is expected to capture the revenue currently generated by traditional products.

According to Romeu Schneider, president of the Tobacco Sector Chamber — an advisory body linked to the Ministry of Agriculture that brings together industry and tobacco-grower representatives — the rise of vapes is reminiscent of the emergence of what is now the conventional cigarette, once known as the “paper cigarette, ” which decades ago supplanted the consumption of palheiros and twist tobacco.

A member of Afubra’s board since the 1980s, Romeu Schneider, president of the Tobacco Sector Chamber, is one of the industry’s veterans (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

“This migration will also happen, in our view, with electronic smoking devices, ” says Schneider, who chaired Afubra. “We believe the consumer will determine this shift from one form of consumption to another and, obviously, suppliers will need to gradually adapt. ”

For many decades, twist tobacco — a darker, more rustic variety used in palheiros and cigars — was produced mainly in the interior of Alagoas, in Brazil’s Northeast. But starting in the 1990s, the market contracted, and today only a few hundred farmers remain in the trade, struggling to survive. With low demand, each hectare planted brings in just US$ 1,800 in gross income for an entire harvest, Joio reported. In that region, not even the PNDACT initiatives — largely focused on the South — ever arrived.