Less tobacco, more nicotine: how the cigarette industry is planning for vape crops in Brazil

Tobacco companies promise a “new source of income” for farmers through nicotine for vapes. Exclusive documents show that those devices require very few farmers and crops different from those traditionally cultivated in the country.

In the late 1970s, veteran Benício Werner, 77, director of the Brazilian Tobacco Growers Association (Afubra) for 50 years, took cigarettes to a compounding pharmacy. The objective was to find out how much tobacco they contained and cross-check that data with sales figures. “If you can calculate averages, you can do the math and alert the producer, ” he explains. “We have to know how much demand there is in order to adjust production. ” It’s simple market logic: a controlled supply of tobacco means a better price when the time comes for the farmer to sell the leaves.

But with the global rise of electronic smoking devices, the rules have changed. Banned in Brazil since 2009 by decision of the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa), they have batteries and coils instead of paper and filters. It’s also hard to tell if they contain tobacco. Many use nicotine, the highly addictive substance found in the leaf and traditional cigarettes. In vapes, it is mixed with chemicals and flavorings, but it is not necessarily extracted from tobacco. It can be sourced from leaves with high concentrations of the molecule, or synthesized in a lab.

The tobacco industry, rather than explaining to growers what impacts the novelty could bring to their livelihoods, has chosen to keep them in the dark. “Technical knowledge, accurate information—this is all widely unknown to us,” said Afubra president Marcílio Drescher. The association, created to guarantee rural insurance to tobacco growers in the 1950s, supports the legalization of these products, provided they use Brazilian tobacco and the farmers do not lose their market. “We don’t know exactly how the industry wants to bring this nicotine to the market”, he states.

Former president of Afubra, Benício Werner, observes electronic cigarettes obtained by the entity abroad under the watchful eye of Marcílio Drescher, current president (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

In Brazil, these products – all illegal – are used by 2.2% of the population every month, a total of around 4.2 million people, according to the Ministry of Justice. With an eye on this market, companies such as Philip Morris International (PMI), who owns Marlboro, and British American Tobacco (BAT), and manufacture brands such as Kent and Lucky Strike, have been lobbying strongly against Anvisa restrictions. The two tobacco giants claim that vapes would increase farmers’ income.

“To us, and even for the tobacco farming sector, extracting this nicotine in Brazil would be very beneficial,” said BAT executive Lauro Anhezini Júnior in 2023 during a Senate hearing.

However, a series of internal documents obtained from U.S. electronic cigarette manufacturer JUUL, obtained by Joio, reveal that Brazilian tobacco growers have much to lose as vapes advance. These include meeting minutes, emails, slides, and spreadsheets made available by the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents website, run by the University of California, which gathers industry files obtained from lawsuits. JUUL has paid over 460 million dollars in damages in the U.S. for causing the addiction of young people to vapes. One of the penalties was to make its internal data public.

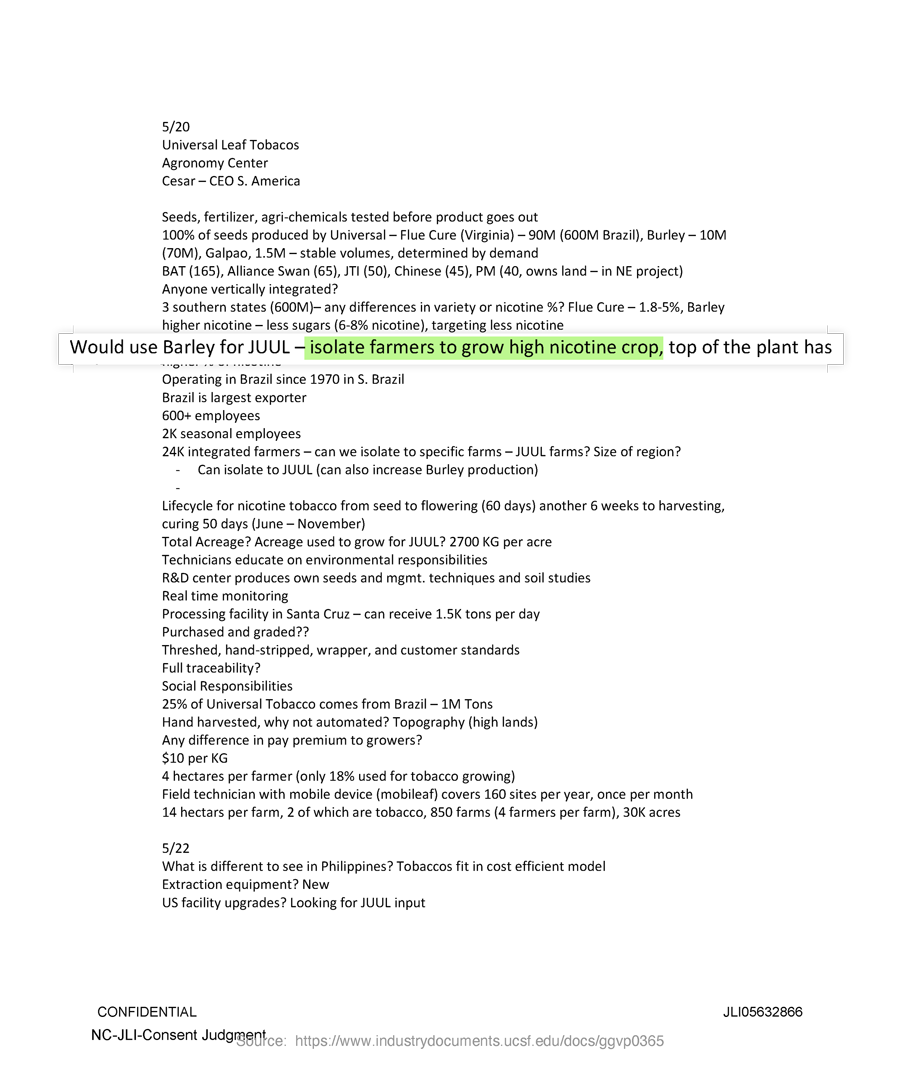

Several of these documents refer to negotiations carried out in Brazil. In 2019, one of the main tobacco suppliers for the cigarette industry, the Universal Leaf multinational company, whose largest agronomic research unit in the world is located in Brazil and has BAT among its clients, proposed to supply JUUL vapes with Brazilian tobacco. The report obtained access to a file detailing the plan, along with estimates and assessments on how the purchase of Brazilian tobacco would be carried out.

The project included restricting production aimed at electronic devices to “specific” farmers who would grow “high-nicotine crops”. In Brazil, tobacco production operates under an integrated system in which tobacco companies decide which varieties the farmers “under contract” should plant and which guidelines to follow.

They provide supplies, seeds, training and deduct these costs from the final payment for the tobacco at the end of the harvest. In other words, only selected farmers would take part in this market.

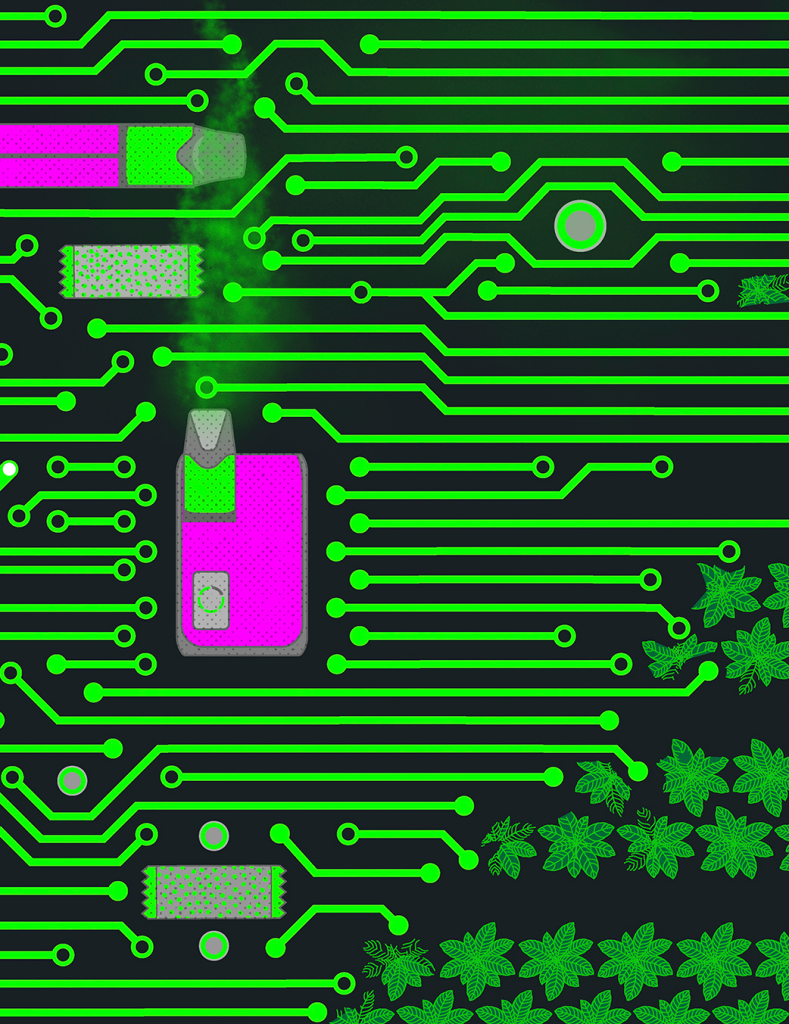

There are currently over 138,000 tobacco growers in the country, most of them small farmers in the South – around 24,000 of which are “integrated” with Universal Leaf. According to estimates calculated by us, around 600 growers – less than 0.5% of all tobacco farmers – would already be enough to supply the global operation of a large-scale brand like JUUL.

In total, 1,600 tons of burley tobacco, a variety whose nicotine content is twice that of Virginia tobacco (the most widely grown in the country), would yield 100 tons of pure nicotine. This corresponds to less than 3% of Brazil’s national burley production.

These numbers are concerning for rural communities—if the public statements of tobacco companies are to be taken seriously. You can check Joio’s estimates here.

Since cigarette consumption continues to decrease worldwide, the industry has been looking for ways to slow down the decline in long-term profits. That’s why tobacco companies have been betting their chips on new products, such as electronic devices. It so happens that this “lifeboat” does not accommodate traditional tobacco farming.

On paper, multinationals pledge to encourage smokers to abandon traditional cigarettes and invest in “less harmful” alternatives. BAT has made the promise that by 2035, it intends for half of its profits to come from new products like vapes and nicotine pouches. In 2023 this share of revenue was 19%.

Philip Morris, on the other hand, say they are “determined to do something very drastic – to replace cigarettes with smoke-free products,” according to emails sent to Brazil’s Ministry of Justice requesting meetings to present the company’s “mission and strategy.” The company’s global goal to become a “smoke-free” company was announced in 2016. In 2023, the company stated its aim for pouches and vapes to account for two-thirds of its profits by 2030.

In terms of impact on rural areas, the long-term plan of these companies includes promoting a shift from a crop that requires 138,000 tobacco growers to one that requires some hundreds of growers.

In October 2024, Joio published details of another internal study made by JUUL which found that as demand for electronic devices overtakes that of conventional cigarettes globally, vapes are expected to create only 24,800 agriculture jobs from 2015 to 2045. On the other hand, the sector would lose 3 million tobacco farming jobs along the way. “The commercial success of JUUL’s entry into new markets will replace locally grown tobacco with globally sourced nicotine,” predicted one of the company’s executives at the time

The differences are so blatant because as there is no combustion in electronic cigarettes, the substances are inhaled much more efficiently. The type of nicotine used in vapes—nicotine salt—is also more addictive than the kind found in traditional cigarettes. Overall, in a direct comparison between a pod and a pack of cigarettes, the device uses up to 24 times less tobacco leaves, despite having a higher addiction potential, according to JUUL numbers reviewed by Joio.

The estimates of few jobs created by vapes contradict the official narrative of the sector in Brazil, which claims that if legalized, the devices would bring more jobs to family farming. A study conducted by the Federation of Industries of the State of Minas Gerais (FIEMG), but funded and promoted by BAT in 2024, claims that their legalization could generate up to 124,000 jobs in the country, including in rural areas.

Joio applied the same calculation methods used in JUUL’s estimates for the demand projected by BAT and reached much lower figures: around 90 producers would already be enough to supply the national nicotine demand projected by the company.

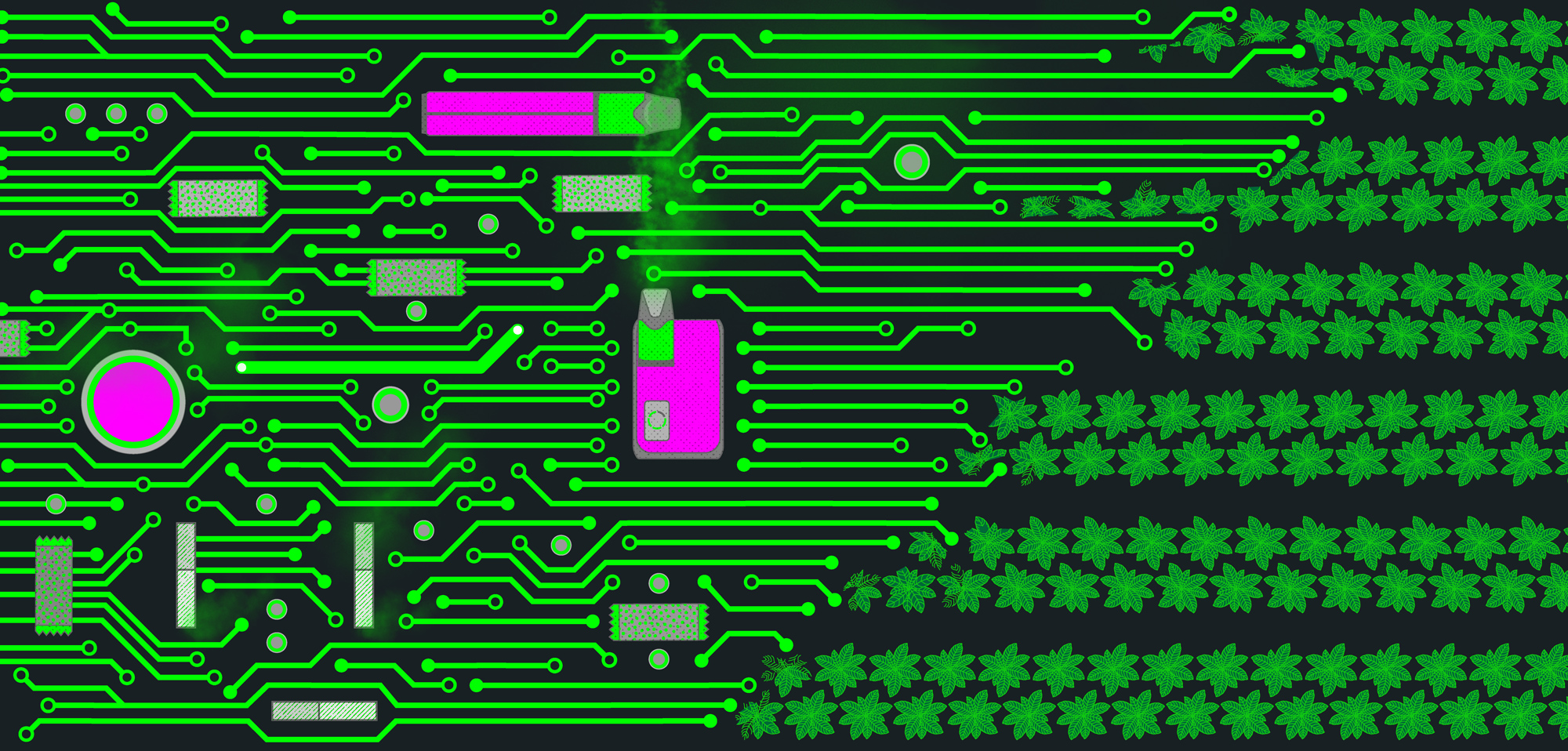

A pod uses up to 24 times less tobacco leaves than a pack of cigarettes, according to JUUL (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

The scenario is so drastic, that even being as low as it is, these forecasts may be overestimated. This is because the tobacco company’s projections are based on a hypothetical scenario that ignores the impact of smuggling on the consumption of electronic cigarettes – and assumes that if Brazil legalizes them, 100% of the market would be controlled by formal companies, which is unrealistic.

At a global level, illicit vapes -manufactured in China at an extremely low cost—tend to dominate markets. In the U.S., for example, around 86% of electronic device sales are illegal products, according to Truth Initiative, a traditional American anti-tobacco NGO.

The BAT study, for example, works with the assumption that a regular product would cost, on average, US$ 27. Another estimate conducted by a team at the University of São Paulo (USP), funded by Philip Morris, projected that legalized electronic cigarettes could cost between US$ 26 and US$ 78. Today, in Paraguay, it is possible to find synthetic nicotine vapes for prices as low as US$ 1.

Universal Leaf did not answer an attempt by Joio to contact them via a form on their website. BAT, through its press office, provided a copy of the FIEMG study report. However, the company chose not to answer the questions submitted by the reporters. Philip Morris, on the other hand, ignored the team’s inquiries entirely.

In May 2019, a group of three JUUL employees landed in Santa Cruz do Sul, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul – a town known as the “national tobacco capital” for hosting multinational tobacco companies and sector entities such as Afubra. At the invitation of Universal Leaf, the three professionals visited farms, processing units, and company research centers, according to emails reviewed by the report.

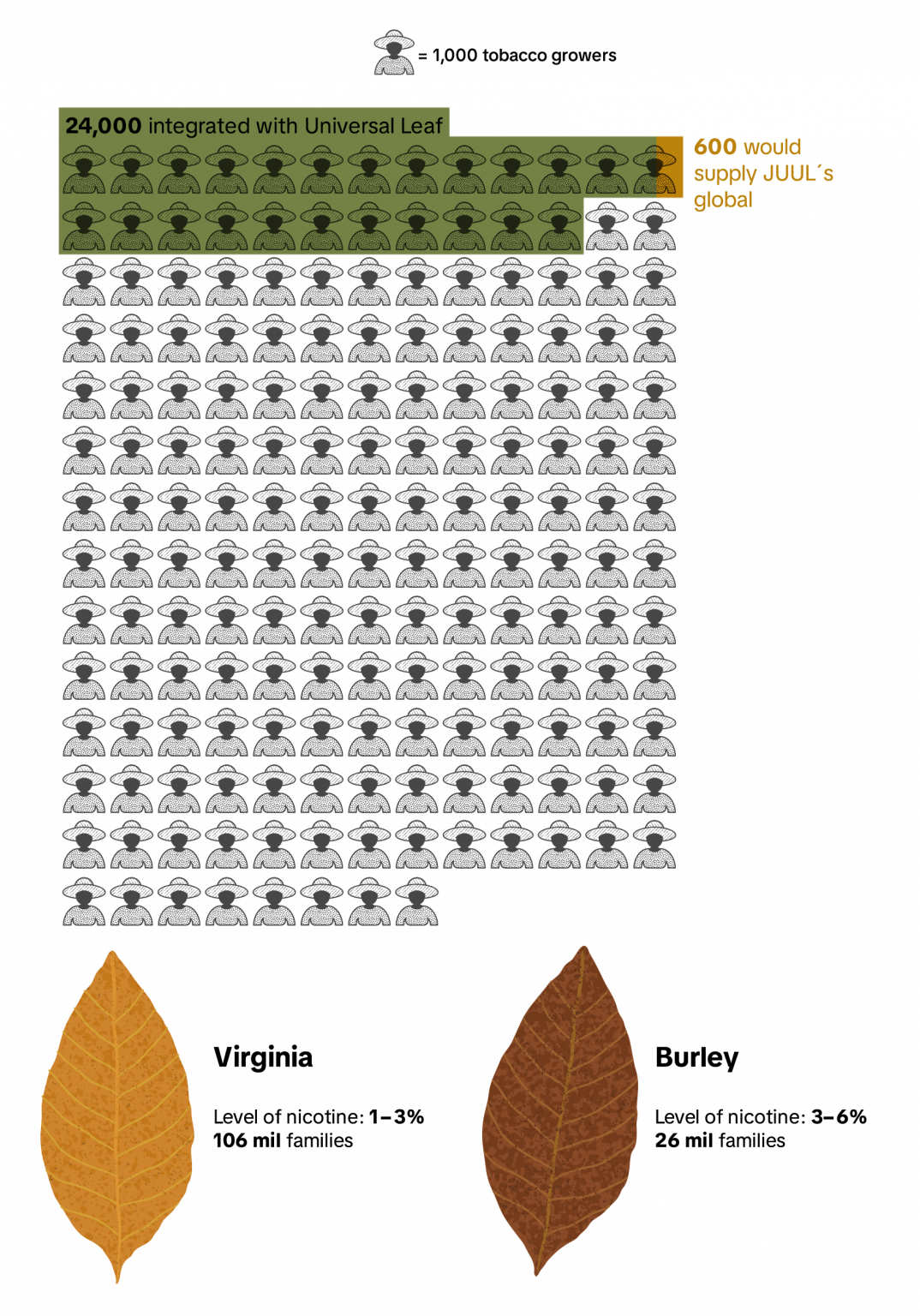

The motivation for the trip came from a proposal by the tobacco company titled “the future of nicotine.” In a presentation obtained by Joio, Universal Leaf lists the value of tobacco, the nicotine content in the leaf, and the costs of extraction and purification as the three main factors that make up the “price of nicotine.” A chart listed tobacco varieties and the countries where they are grown. Four of the five cheapest options came from India. Brazil ranked seventh. Yet, even without having the best cost, Universal Leaf favored Brazil and wanted to convince JUUL of that.

“Why Brazil? First: higher nicotine content [in the leaf], location of the extraction facility, no licensing issues, faster product launch, strong political connections,” company executives told the vape brand trio, according to the minutes of one of the meetings held in the southern Brazilian town. In other words: in Brazil, the brand would benefit from favorable logistics, would not face regulatory hurdles to extract nicotine from the leaf, and would have political support.

Apresentação da Universal Leaf à JUUL traz argumentos para fixar cadeia global da empresa de vapes no Brasil

In a second document, a JUUL employee recorded notes from the meeting detailing how Universal Leaf intended to make its integrated farmers available to the company. “[Universal] would isolate farmers to grow high-nicotine crops,” he wrote. “We could isolate [production] to specific farms – JUUL farms?” he continues. The notes later confirm that this was indeed the case.

To that end, they would select dark burley tobacco, more precisely the KY 171 variety, which is neither harvested in Brazil nor registered with the Ministry of Agriculture. Burley is a type of tobacco grown by less than 25% of Brazilian producers, usually in regions near the Argentine border. Unlike Virginia tobacco, the most widely cultivated and exported variety in Brazil, burley is cured in barns, not wood-fired kilns, and is harvested whole, not leaf by leaf. The price paid to the producer is, on average, 14% lower.

But Universal Leaf’s plan did not succeed. JUUL preferred, in the short term, to use Indian nicotine, produced at a low cost using leftovers from the industrial processing of bidi, a traditional tobacco product in that Asian country, and to bet on lab-produced synthetic nicotine in the long term. The visit to Rio Grande do Sul was, in fact, just to gather insights about the market. “This trip is to observe their (Universal’s) leaf extraction process firsthand,” said a JUUL employee in an email discussing the trip to Brazil.

“World leader in the leaf tobacco business,” reads the facade of the Universal Leaf facility in Santa Cruz do Sul (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

At that time, the company was even considering contracting Universal Leaf as a supplier but preferred to set up operations in Asia, in locations such as the Philippines or Indonesia. The fact that electronic cigarettes have been banned in Brazil since 2009 didn’t help. “Kevin [Burns, then CEO of the company] is not optimistic about this country and basically sees it as a money sinkhole (to paraphrase),” wrote a JUUL executive in one of the email exchanges.

One of the key factors that convinced JUUL to prefer synthetic nicotine over the tobacco-derived variety in the long run was precisely the cost. At the time, the lab-produced substance was more expensive due to lack of scale—the market was still largely dominated by low-cost Indian bidi. However, JUUL’s spreadsheets indicate that for the demand the brand projected, while Universal’s nicotine was expected to cost up to US$ 350 per kilo, the synthetic version could be negotiated for around US$ 300 if purchased in larger volumes.

“THE INDUSTRY IS LIKELY TO TRY TO DISASSOCIATE NICOTINE´S IMAGE FROM TOBACCO, IN A EFFORT TO SHOWCASE THE SUBSTANCE IN A MORE POSITIVE LIGHT”

– Erwin Henriquez, from Euromonitor

A source connected to a nicotine manufacturer interviewed by the report said that six years after JUUL’s estimates, the costs of producing synthetic nicotine are now lower. It is this lower pricing, for example, that ensures scale and competitiveness for vapes produced in China, which dominate both legal markets such as the U.S. and illegal ones like Brazil.

“Synthetic nicotine is much cheaper,” as confirmed to Joio by senior nicotine industry consultant Erwin Henriquez, from Euromonitor, an international business intelligence consultancy that advises various industries, including tobacco. “In fact, this is one of the reasons why products such as disposable vapes can be produced on such a large scale and so quickly.”

In Henriquez’s view, synthetic and tobacco-derived nicotine will attract different consumer profiles in the long term, and the very idea of tobacco being synonymous with nicotine will lose ground. “The industry is likely to begin to try to disassociate nicotine’s image from tobacco, in an effort to showcase the substance in a more positive light” says the consultant. “Overall, I believe the share of synthetic nicotine in the global market will grow steadily over the next five years, gaining significant market share, especially as the industry continues to disconnect nicotine consumption from combustion and increasingly, from tobacco itself.”

The short-term impact, however, will be minimal. “The big tobacco companies have very strong control over the global tobacco leaf supply chain, so it’s in their interest to maintain this structure as an entry barrier for smaller new competitors who could threaten their position,” he assesses. Additionally, regulators may try to favor tobacco-derived nicotine to prevent the spread of lab-produced alternatives.

Most e-cigarettes use parts produced in China. In some cases, "illicit" vapes and those produced by multinational companies use the same Chinese suppliers (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

Nevertheless, Universal Leaf’s project did not die with JUUL’s rejection. On the multinational’s team that participated in the 2019 meetings was Valmor Thesing, the company’s administrative director at the time.

Years later, in 2024, he left the position to become president of the Interstate Union of Tobacco Industries (SindiTabaco), an entity that brings together the main companies in the sector in Brazil, including Universal Leaf itself, and is one of the organizations responsible for lobbying on behalf of tobacco with politicians, governments and the media. SindiTabaco confirmed Thesing’s participation in the meetings with the vape brand to Joio.

“At that time, JUUL was prospecting future suppliers of raw materials at an international level, and one of the selected companies was Universal Leaf through its U.S. headquarters,” said the entity in a statement. “Due to contractual confidentiality commitments, which remain in effect after the executive’s departure, there are no comments to be made regarding the content of the company’s internal meetings.”

Since he took over as president of SindiTabaco last year, one of Thesing’s main arguments in favor of the legalization of electronic cigarettes has been that they would open the Brazilian market to the production of tobacco-derived nicotine.

“I believe Brazil is missing out on a major opportunity to enter this new market by not legalizing the end products [vapes] here,” Thesing told Joio at the end of March. That was just weeks before Truth Tobacco Industry made the documents detailing his meeting with JUUL public: “I’m referring to the production of liquid nicotine and other by-products of the leaf, which Brazil has in abundance, and we’re discussing this due to an Anvisa resolution that makes no sense,” he stated.

In response to us, however, Anvisa said that it “does not establish rules for how nicotine is extracted from the plant” nor does it “regulate the extraction of the substance.” In other words, the country has no restrictions on the production or export of pure nicotine—only on its “conversion into a smoking product,” that is, its mixture with solvents to produce the liquids used in electronic devices.

Brazil’s situation is roughly the same as in India, the world’s largest manufacturer of this product. Vapes were banned there in 2019, but Indian-origin nicotine supplies most of the global market. The conversion of the country’s crude nicotine into e-liquids is often done in facilities in China, the US, or Switzerland.

Cut rag tobacco in Brazilian industries goes straight to cigarettes, but byproducts such as dust and stem could be used to produce liquid nicotine – a process not currently done in Brazil (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

SindiTabaco, however, blames Anvisa for the “missed opportunity.” The entity told Joio that even though the agency does not ban nicotine extraction itself, it prohibits its export if the intended commercial use of the raw material is for producing vape liquids. At the same time Universal Leaf was presenting its plan to JUUL, the company reportedly sought authorization from Anvisa to produce and export liquid nicotine, but the request was denied, and “the prospecting study” was shut down, said the union.

Additionally, the entity claimed that the preference for burley tobacco “would be an opportunity for these producers, who had been facing a decline in demand, to continue producing.”

As a result, the promise of income for rural producers through nicotine extraction has become an argument for vape legalization used by politicians who claim to defend tobacco growers. The discourse gained traction, for example, in the Legislative Assembly of Rio Grande do Sul, the state that is the largest tobacco producer in Brazil, responsible for about 40% of national production.

In early July this year, state representatives in Rio Grande do Sul approved a report, supported by SindiTabaco and BAT, which suggested that vapes could protect tobacco farming from the global decline in tobacco consumption. “Tobacco producers and associated industries have limited potential for innovation and diversification, which exacerbates their dependence on traditional markets that are facing a global decline in conventional cigarette consumption,” the document states.

“By regulating ENDS (Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems) and promoting the production of liquid nicotine extracted from tobacco agriculture products, Brazil would be creating a new source of income for the sector,” assures the report. Its author, state representative Marcus Vinícius of the Progressives (PP), did not respond to Joio’s interview requests.

Concern about the sector’s future does have some grounding, as governments around the world have been striving to curb cigarette consumption. The product kills more than 8 million people per year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). That number surpasses the total deaths from the Covid-19 pandemic, which claimed approximately 8 million lives between 2020 and 2023. In Brazil alone, 161,000 deaths per year are linked to smoking, according to the National Cancer Institute (Inca).

It’s therefore no surprise that global cigarette consumption dropped from 5.9 trillion units in 2007 to 5.1 trillion in 2020, a decline driven by public health measures, according to tobacco industry yearbooks reviewed by Joio. The decline in demand has also impacted the number of tobacco farmers in Brazil: there were 236,000 growers in 2005, 71% more than today.

The world’s largest tobacco exporter, Brazil has also seen its exports fall. From 626,000 tons in 2005 to 446,000 in 2024, according to export data from Brazil’s Ministry of Development, Industry, Commerce, and Services.

Lara shows one of the byproducts of tobacco processing, dust. It can be used to produce everything from liquid nicotine to reconstituted tobacco—an "ultra-processed" version of the leaf that can be used in regular cigarettes or electronic devices (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

While multinational companies lobby for the legalization of electronic devices to open up this market in Brazil, smaller companies are already moving to export Brazilian tobacco and meet the demand for pure nicotine, which can also be used in heated tobacco devices and nicotine pouches, both popular in various countries in Asia and Europe. One such company is Unicruz, a tobacco processing company based in Vera Cruz, a town near Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil’s so-called “tobacco capital.” The company is developing projects for the purchase and sale of tobacco for nicotine extraction.

The lack of cultivation of high-nicotine varieties – such as the one planned by Universal Leaf – is, however, an obstacle. “They’re looking for tobacco with very high nicotine content, which we don’t grow here as in other countries,” explains Jonas Lara, Unicruz Director of Operations. “Today, the tobacco planted in Brazil is intended directly for cigarettes, but over time, they’ll likely start producing a variety with higher nicotine levels,” he evaluates.

Farmer Ernani Konzen, 50, watches over part of the eight hectares of his fields—five owned, three leased—where his family will plant around 100,000 tobacco plants this season. He, his 21-year-old son João, and his 41-year-old wife Cristiane have been growing tobacco leaves there for the past 14 years, currently supplying BAT and Philip Morris.

The family, living in a rural area of Santa Cruz do Sul, struggles to make a living from crops other than tobacco on their small plot of land. “I tried growing corn years ago and ended up having to pay to grow it, because when the time came to sell, the price didn’t cover the production cost,” says Ernani. “The only thing that makes us money, profit, today is tobacco.”

The Konzen family surveys part of their eight-hectare tobacco farm. The work is overseen by Ernani, Cristiane, and their son, João (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

In several tobacco-growing regions of southern Brazil, producers who “venture” into other crops face difficulties, as the entire economic logistics in many of these towns is centered around the tobacco production chain. In municipalities such as Vera Cruz and Santa Cruz do Sul, for instance, most local markets purchase food over 150 kilometers away, from supply centers in the capital city of Porto Alegre, rather than from local farmers.

Brazil does have a public policy – the National Program for the Diversification of Tobacco- Cultivated Areas (PNDACT) – designed to help tobacco farmers find alternative sources of income apart from tobacco, given that with the decline in traditional cigarette consumption, the long-term trend is a drop in demand for the leaf. The program had several editions between 2011 and 2019, but never really took off. Today, it remains shelved under President Lula’s administration at the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA).

Still, there is no clear understanding among farmers about what electronic cigarettes are and what risks they might pose to their crops. “We hear about it in the media, but as far as the companies go, they haven’t shared anything about it with us yet”, says Ernani. “The only thing they say is that farmers who produce quality will never need to worry because they’ll always have a market.”

Even politicians who support tobacco farming, such as federal congressman Heitor Schuch (PSB) – who is from Santa Cruz do Sul – have not received clear answers from the industry when questioning whether electronic cigarettes require less tobacco than traditional ones. “The impression is that there’s still very little concrete data on the real impact of electronic devices on tobacco demand,” he said in a statement to Joio. “Farmers, in general, want to produce and earn a living to support their families—they’re not directly involved in this debate.”

João Konzen shows tobacco plants that the family will supply to BAT and PMI (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

At the end of March, SindiTabaco president Valmor Thesing, who participated in the Universal Leaf meetings with JUUL, told Joio he did not have “technical data” on whether liquid nicotine requires fewer leaves to be produced, and said the entity would begin a “dialogue” with the tobacco companies to discuss the issue with farmer representatives.

The union leader also suggested that a decline in tobacco demand and its impact on rural production would be “excellent for Brazil.” “Our government only says we should ‘diversify’ the producers—in other words, we should end tobacco production so that they produce food,” he said. “So, if the number of producers needed for tobacco is reduced, we’ll put diversification in place and give the government what it wants.”

Throughout the conversation, Thesing hinted that with electronic cigarettes, the sector is eyeing the ‘smokers of the future.’ “Do you believe future generations will smoke traditional cigarettes – if they even smoke – or will they use new products? Who decides what will be consumed? The industry or the user?” he asked. “Humankind cannot live without vices.”