BAT inflate data to promise jobs if vapes are legalized in Brazil

Company claims the devices would create 13,000 new jobs in rural areas, but BAT’s e-cigarettes are manufactured in China and, even if they used nicotine extracted from Brazilian tobacco, production would require fewer than 100 farmers.

From a corporate rooftop at the high-end Carlton Tower in Brasília—overlooking the headquarters of Brazil’s largest public banks—tobacco industry lobbyist Lauro Anhezini Júnior presented grandiose figures to state deputies from Rio Grande do Sul in a hybrid legislative session in October 2024.

Around US$ 254 million in revenue, 12,950 rural jobs created, and at least US$ 12 million more in farmers’ pockets if vapes—banned in Brazil since 2009 by the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) —were legalized. Brazil would even have the potential to become an exporter of e-cigarettes, doubling those numbers, the executive promised.

“It has been economically proven that regulating e-cigarettes in Brazil would be widely favorable to national tobacco farming, generating jobs, income, and significant revenue for the sector, ” said Anhezini, who is both director of the Brazilian Tobacco Industry Association (Abifumo) and of British American Tobacco (BAT) —formerly Souza Cruz, and manufacturer of brands such as Kent and Lucky Strike, as well as the phased-out Derby, Free, and Carlton. The data came from a study by the Federation of Industries of the State of Minas Gerais (FIEMG), commissioned by BAT itself.

This initiative clashes with public health organizations’ warnings that vapes intensify nicotine addiction—especially among youth, given their strong appeal to younger generations. In 2024, eighty medical associations signed a letter opposing legalization in Brazil. “The profile of users of these devices is different from the classic smoker: it is a population with high education levels and income, concentrated among girls, teenagers, and young adults,” says epidemiologist André Szklo, of the National Cancer Institute (Inca). “[If legalized] we will be adding a new profile to Brazil’s tobacco epidemic.”

Anhezini attended the legislative session—which had created a “Subcommittee on the Regulation of Electronic Smoking Devices and Protection of the Tobacco Production Chain” with industry support—to explain how vapes could boost Rio Grande do Sul’s fragile economy. The billions he cited dazzled state politicians, given that multinational tobacco companies operate factories in municipalities like Santa Cruz do Sul and Venâncio Aires, and the state is home to about 70,000 tobacco farmers—nearly half of Brazil’s total 138,000.

There are 138,000 tobacco farmers in Brazil today, according to Afubra (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

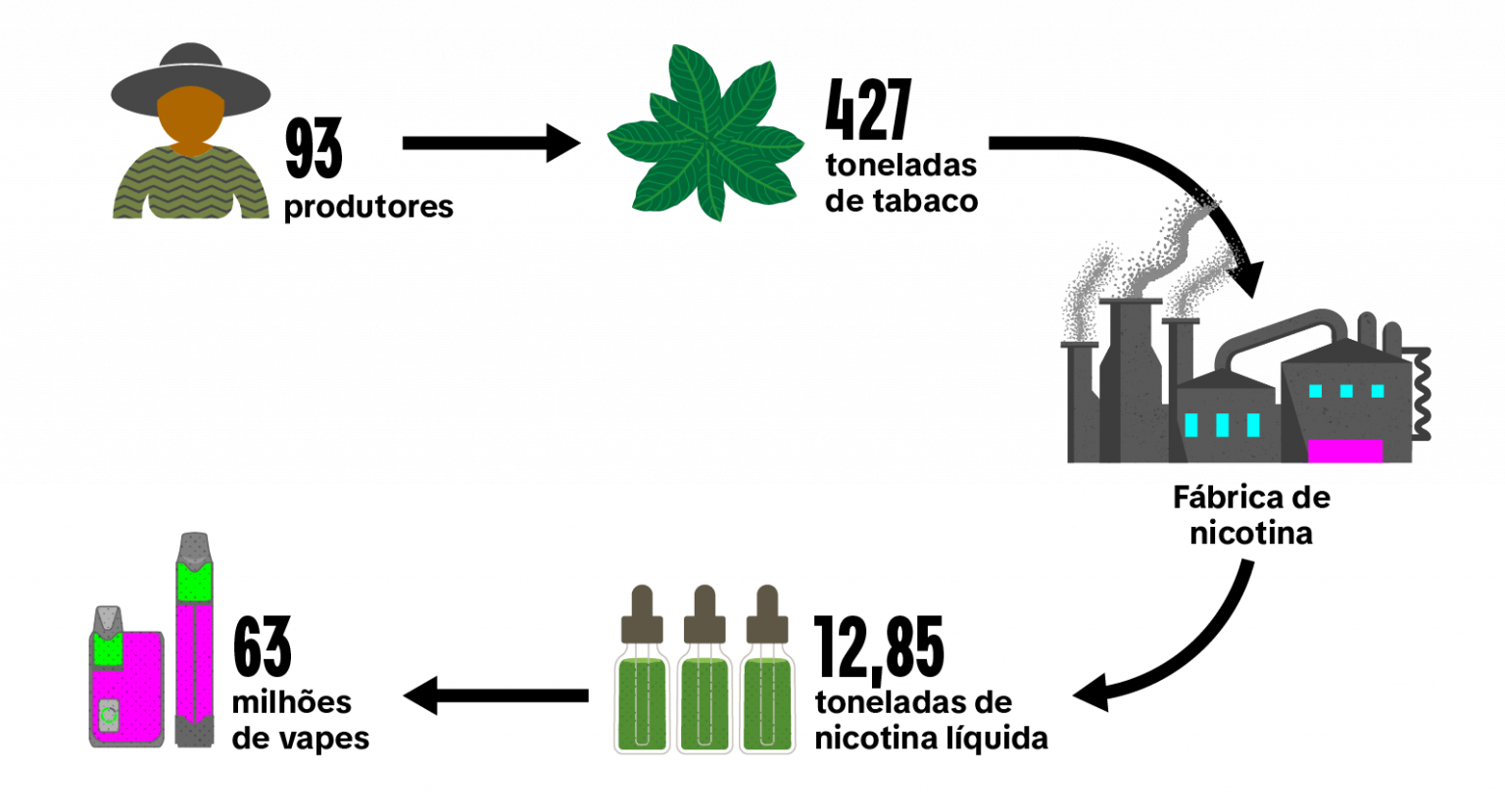

What Anhezini did not tell those lawmakers, however, is that if the multinational decided to supply its vapes with nicotine extracted from Brazilian tobacco, the number of farmers required would be minimal: only 93 tobacco-farming families, according to Joio’s analysis. And not the almost 12,900 jobs promised to the Rio Grande do Sul deputies.

Based on internal documents from U.S. e-cigarette manufacturer JUUL—including calculations of the tobacco required to produce its liquid nicotine—Joio estimated that fewer than 100 farmers would be sufficient to meet BAT’s projected demand under a legalization scenario. That is, if the company even used Brazilian tobacco—since in products sold on other continents, BAT relies primarily on Indian suppliers.

Moreover, BAT’s e-cigarettes sold in Latin America are manufactured in China, by the same companies that produce the illegal brands flooding Brazil’s black market. In other words, they would not generate jobs domestically.

To arrive at this estimate, Joio drew on FIEMG’s consumption projections and applied JUUL’s internal formula. Using data from the Brazilian Tobacco Growers Association (Afubra), the report then calculated how many farmers would be required to supply enough tobacco leaf to produce the liquid nicotine for vapes comparable to BAT’s global brand, VUSE.

In total, just 427 tons of Virginia-type tobacco— an output typically produced by 93 farmers—would be enough to yield 12.85 tons of pure nicotine, sufficient to meet FIEMG’s projected consumption of about 63 million vapes annually.

In practice, a single farmer could supply enough raw material for 676,000 e-cigarettes—equivalent to the annual consumption of 37,500 smokers. The methodology and the calculations made by Joio can be found in the following link.

Labor requirements are so low because producing pure nicotine involves extracting and purifying the substance from the leaf, after which it is mixed with chemicals and flavorings to make the liquids used in these devices. In traditional cigarettes, by contrast, much of the nicotine is lost during combustion. In a direct comparison between a pod and a pack of cigarettes, e-cigarettes contain 8 to 20 times less raw nicotine, according to JUUL’s internal estimates reviewed by Joio. When measured in terms of leaf volume, vapes require up to 24 times less tobacco. This does not mean that they are less harmful.

The report’s estimate also assumes that the tobacco used in these products would be cultivated by farmers dedicated exclusively to nicotine production for vapes, following a model once considered by multinational Universal Leaf to supply JUUL with Brazilian nicotine. The U.S. company’s documents were obtained through the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents archive at the University of California, which compiles industry records made public through U.S. lawsuits.

Another possibility, if the devices were legalized, is that BAT would use nicotine extracted from tobacco-processing residues—a byproduct with a lower nicotine content but far cheaper. This is the same model followed by Indian industries, where nicotine manufacturers purchase Bidi tobacco powder directly from processors.

Even with these already discouraging figures for rural areas, the employment projections may still be overstated. That is because FIEMG’s estimates assume an “ideal” scenario where vape smuggling ceases to exist. “This study assumes that potential demand for e-cigarettes—once legalized—will be fully met by the lawful tobacco industry,” the federation acknowledges in its “limitations” section. A presentation with the study’s data was provided to Joio by BAT.

“They project sales I’m not too sure a legal product would have,” says economist Roberto Iglesias, a World Health Organization (WHO) consultant and expert on illicit tobacco trade, who reviewed the BAT/FIEMG slides at Joio’s request. “They also talk about jobs and payroll, but hidden behind it is the idea that a new vape production hub would emerge here, when in fact what they would really do is import Chinese parts and assemble them locally.”

The company’s calculations estimate that each “legal” e-cigarette would retail for US$ 27, overlooking the fact that illicit vapes cost as little as US$ 1 wholesale in Paraguay—the main source of contraband cigarettes in Brazil, both conventional and electronic. Once in Brazil, however, most devices sell for over US$ 18. Legalization, therefore, could boost sales of cheaper illegal vapes and expand consumption beyond the upper middle class. “One possibility is a price war,” Iglesias warns.

Asked by Joio, BAT declined to answer questions about the study and indicated that any questions should be directed to FIEMG. The federation stated in a note to the press that “the approach used in the study is based on economic scenarios that seek to assess the direct and indirect effects on the economy as a whole.” “It is, therefore, a macro-level analysis, without going into specific production data per company,” it said.

Na fachada de sua unidade em Santa Cruz do Sul (RS), em meio a um logotipo enfeitado por um arco-íris, BAT diz estar “construindo uma trajetória de pioneirismo por um amanhã melhor” (Fotos: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

Since 2023, BAT has released at least two different versions of the study, each offering new promises tailored to different audiences. Initially, the company claimed vapes would create a US$ 1,3 billion market, estimating that 3.3 million Brazilians would each consume 15 devices per year, a figure repeated in cigarette-industry-sponsored events and in the Brazilian press. By April 2024, the projection had risen to 3.5 million consumers, 18 vapes per year, and US$ 1,9 billion in revenue.

The multinational’s figures, however, model vape demand as though production were comparable to traditional cigarettes. “The economic and social impacts analyzed are directly and indirectly linked to an increase in production within the tobacco-products sector, aimed at meeting potential demand for e-cigarettes,” the study’s presentation explains.

Unlike conventional cigarettes, which use filters, paper, and shredded tobacco, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) require batteries, coils, and liquids containing nicotine—either extracted from tobacco or synthesized in laboratories at pharmaceutical-grade facilities.

Most of these factories are located in Shenzhen, China, an industrial hub for electronics production. In Brazil, BAT’s brands such as Kent and Lucky Strike use tobacco grown in the South and are manufactured in its plant in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais—representing a very different production chain.

In the same hybrid session of Rio Grande do Sul’s Legislative Assembly, Abifumo and BAT director Lauro Anhezini Júnior argued that banning e-cigarettes creates a scenario of “sanitary chaos” in the country. “Nobody knows what is being consumed; people have no idea about the product’s contents or safety standards,” he said. “When you don’t have rules, product standardization, or sanitary regulation, a public health problem emerges. ”

His slides highlighted Brazilian news reports of vape explosions and cases of young people with “oil” from the devices in their lungs, all of which, he suggested, stemmed from the lack of sanitary control over contraband vapes.

Yet the same Chinese factories that produce some of the most popular illegal vapes brands in Brazil, also manufacture BAT’s vapes. In other words, the supposedly “unregulated” illegal products flooding the Brazilian market share the same origins as the multinational’s legal devices in Latin America. That is the case, for example, with Ignite—one of the leading illicit brands sold in Brazil—which, Joio found, shares suppliers with BAT’s brands.

The illicit vape brand is so well established in Brazil that, despite not officially selling vapes here, it has already launched beverage and clothing lines, even signed singer Gusttavo Lima as a brand ambassador.

To uncover this, Joio purchased an Ignite device at a store in downtown Porto Alegre, confirmed its authenticity on the brand’s official website (yes, illegal ENDS sold in Brazil come with anti-piracy codes), and then checked the manufacturer information on the packaging. Today, most e-cigarette production is outsourced to Chinese companies. In Ignite’s case, the “original product” is a generic white-label version, to which the company simply adds its branding. The manufacturer in this case is VapeEZ Technology, based in Shenzhen—a Chinese city near Hong Kong regarded as the “global capital of vapes.”

Joio then tracked down any online files available mentioning both VapeEZ and Ignite in the same document. This search uncovered a 2025 internal “training” manual from the brand’s Russian subsidiary detailing its production chain. “The liquid [of Ignite] contains flavors and nicotine from major global manufacturers, whose clients include British American Tobacco,” the file states, highlighting Chinese companies VapeEZ Technology and Smoore Technology as suppliers of Ignite vapes.

The reporters then consulted Paraguayan customs data—the main route for illegal vapes into Brazil—that included references to British American Tobacco, VapeEZ, and Smoore. The data, provided to Joio by the trade-intelligence platform ImportGenius, show that BAT imported about 60,000 e-cigarettes from VapeEZ in 2024 and 300,000 from Smoore in 2023.

During the same period, between 2021 and 2023, Smoore also sold Paraguayans thousands of e-cigarettes (or parts for assembly in the country) under the brands Nikbar and Vaporesso, which, after Ignite, rank among the most popular in Brazil’s illegal market.

According to ImportGenius data, aside from BAT, one of the main importers of the Chinese company’s products into Paraguay is Agatres, a vape distributor identified by a 2024 Núcleo investigation as responsible for marketing and smuggling e-cigarettes into Brazil. VapeEZ, on the other hand, did not sell devices to other companies, according to the data reviewed by Joio.

The entrance to Santa Cruz do Sul, the “tobacco capital” of Brazil, carries the BAT logo (Photo: Isabelle Rieger/O Joio e O Trigo)

In response, the tobacco multinational acknowledged its business relationship with Smoore. “BAT acquires its vapor products from different suppliers, including Shenzhen Smoore Technology Limited (Smoore), and the operation between BAT and Smoore follows processes independent of the activities the company [Smoore] maintains with other clients,” the company said in a statement. “BAT states it has no ties to VapeEZ and has never maintained a commercial relationship with the company.”

Joio, however, emailed the Chinese company and mentioned having identified customs data indicating exports to the British multinational. “VapeEZ mainly focuses on ODM products [meaning it manufactures and licenses them] for many branded companies, such as Ignite,” replied a sales team representative. “In addition, we are in communication with BAT on some new projects.”

A recent study by Brazil’s National Cancer Institute (Inca) calculated that, for every US$ 0,20 in profit the tobacco industry makes from conventional cigarettes, the country spends a total of US$ 1 on the direct and indirect costs of smoking, linked to illness, loss of productivity, and death. There are still no calculations estimating the negative health impacts of vapes. However, the trend is that they may drive a return to conventional cigarette use. “You will have part of the population that starts using the electronic device, and once dependence sets in, they will migrate to the cheaper product, which is the conventional one,” says André Szklo of Inca.

Read BAT’s full responses to Joio below:

BAT states that it has no ties to VapeEZ and has never maintained a commercial relationship with the company.

BAT acquires its vapor products from different suppliers, including Shenzhen Smoore Technology Limited (Smoore), and the operation between BAT and Smoore follows processes independent of the activities the company maintains with other clients.

Our vapor devices undergo rigorous quality testing. Each product is subjected to more than 1,000 hours of tests, ensuring excellence in performance and safety.

In addition, our devices are tested and certified by independent laboratories, ensuring that each unit meets the highest standards and complies with local legislation before reaching consumers.